Tickets and transfers from multiple transit operators circa 1890s-1940s. Courtesy Emiliano Echeverria.

Fare collection has long been one of the hottest topics in public transit. Opinions range about how much a ride costs or how much it should cost, who is paying and who is not paying. Often forgotten in all the talk about fares is the history behind Proof of Payment systems, or “POP.”

In this post, the first in a two-part series, we’ll look at tickets and transfers. Tickets and transfers have been in use in San Francisco for over 150 years.

Tickets: the original proof of payment system.

Introduced in the mid-late 1800s, tickets were the earliest form of receipt on SF public transit lines. Simple yet effective, tickets worked well for the limited system of the time. Conductors sold them on transit vehicles as people boarded. Usually, tickets were good for one ride in one direction, with no hopping on and off.

One of Muni’s first female conductors, Ellen Peterson, in 1942. Conductors collected fares, issued tickets and transfers and helped maintain safety on vehicles.

At that time, multiple companies operated separate lines using different types of vehicles. Generally, each transit line ran only on one or two streets. Each company issued tickets that could only be used for their lines. This system worked well for competition but not for people traveling around the city.

This ticket from about 1875 was issued by the Clay Street Hill Railroad Company, San Francisco’s first cable car operator. Ticket courtesy Emiliano Echeverria.

Over time, tickets were mostly phased out in favor of transfers. For many years, transit companies continued to sell tickets for special uses like school trips. These were eventually replaced by student passes.

Today, the only single-use, non-transfer tickets are for one-way cable car rides.

Transfers: expanding travel options in the city.

Between 1860 and 1900 public transit expanded quickly in San Francisco. Paper transfers were introduced as the number of transit companies and lines increased. Transfers allowed people to start their trip on one line, then switch to another to get to their destination.

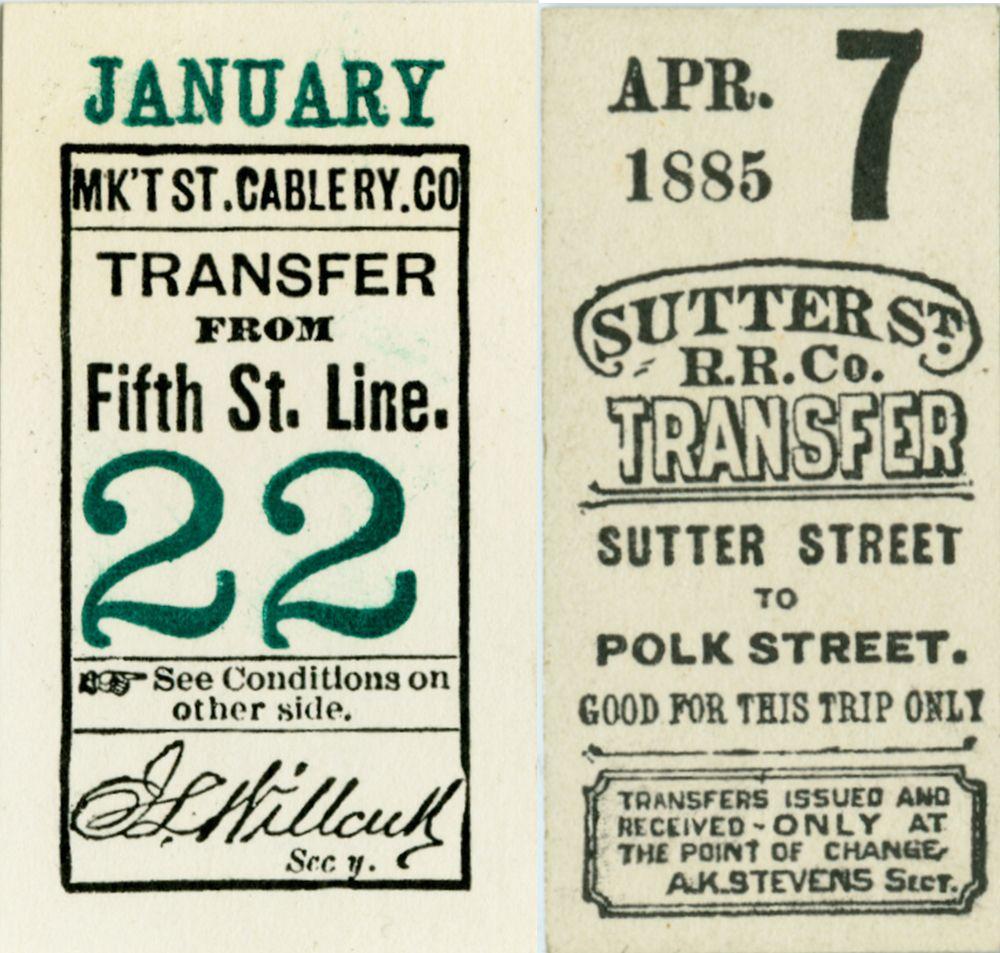

Two transfers from 1885 from the Market Street Cable Railway Company and Sutter Street Railroad Company. Transfers courtesy Emiliano Echeverria.

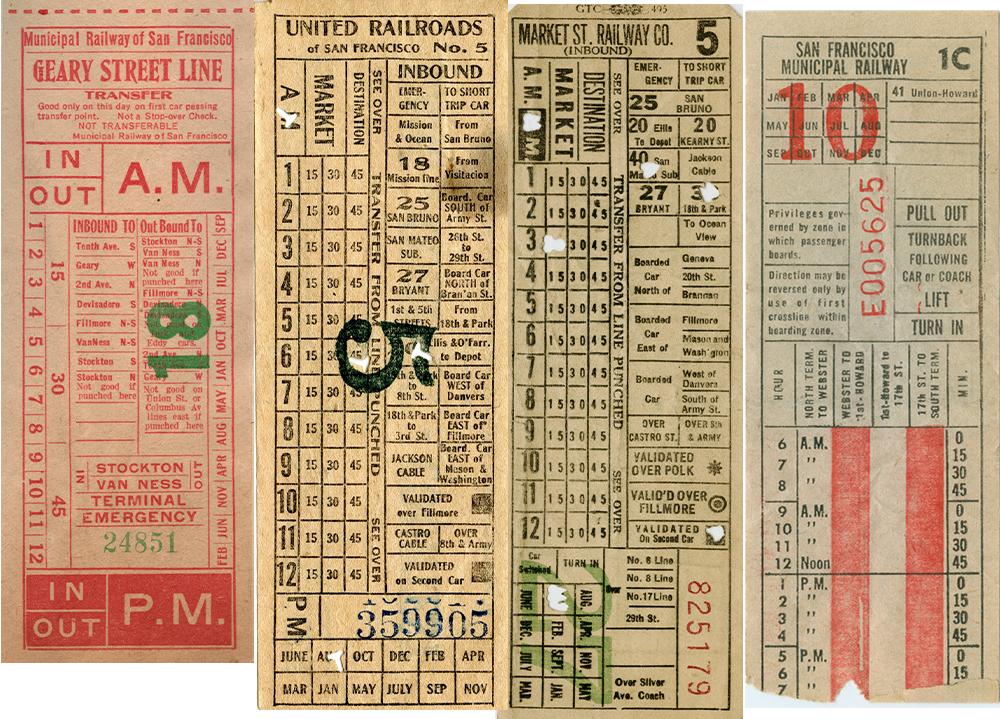

Early transfer rules were complicated compared to today. Each transit company had their own rules and limitations. In some cases, passengers had to turn in their ticket to a "transfer agent" to receive a transfer. It was also common to have to pay an extra fare to receive a transfer.

Transfers between competing lines were rare. To be valid, the line, direction of travel and time were punched out of the paper by the transfer agent or conductor. People could only transfer at certain points along the route or while traveling in a single direction.

Over time, the number of companies operating transit in the city decreased. By the mid-20th century, Muni operated all transit in the city. As competition decreased, transfers became simpler and easier to use, with fewer restrictions.

In the 1950s, Muni introduced the tear-off timed transfer. With this type, an operator tore-off the paper transfer to indicate the time the transfer expired instead of punching all the details of the trip.

In 1975, the tear-off transfer was changed to provide more flexibility for riders. Transferring was no longer restricted to designated stops. People could get on and off anywhere along the line, and they also had more time to change routes or make stop-overs.

Transfers continued to be valid only in one direction of travel. Eventually, the system changed to include unlimited transfers. These were good anywhere in the system during the time marked.

A variety of paper transfers from 1915 to 1970. In the middle are two with travel information punched out by a conductor. On the right is a tear-off type. Transfers courtesy Emiliano Echeverria.

Our agency discontinued tear-off transfers in 2018. You can learn more by reading our blog, New Muni Fare Machines Now Aboard All Buses. With our new fare boxes, Muni customers receive a receipt printed at the time of payment. This receipt is a cross between a ticket and a transfer. They are issued like a ticket but work like a transfer. Valid for two hours from the time of payment, the new system is simple and allows an extra 30 minutes of travel time.

Proof of Payment has changed over time but still serves the same basic function after more than 150 years. Stay tuned for the next post in this series, which will cover the history behind tokens, passes and Clipper.